When we study history in high school, we read about the history of machine guns, cars, printing press, etc. I imagine that some time in the future, students may sit down and read about the early programming languages and their development.

This post is a brain-dump of some fun things I know about Python, most of which are fairly non-technical. These are not the most fun things as I tried to avoid writing about things that were already nicely summarized, but they will at least be tastefully boring!

Inspiration

In the mid 1980s, Guido van Rossum was working on ABC, a generally unpopular high-level language intended for teaching and prototyping. Based on his frustrations with ABC, Guido wanted Python to have a large and powerful standard library. Python (first released in 1991) would soon be joined by Java (released in 1995) in having such a standard library.

Contrary to C, Lisp (and lisp dialects) and Ruby, Python does not allow statements inside an expression. For example, if (x = y) (or more practically, if (line = readline(file))) could be used in C though Python does not allow them. The goal here was probably to make Python easy to use and to protect its users from common errors such as accidentally typing x = y instead of x == y. But also uhh... there's a walrus operator (:=) for assignment expressions in Python 3.8 so maybe I just lied.

From Haskell and Lisp, Python inherited support for functional programming, with filter, map and reduce. Python documentation lists the itertools module under Functional Programiming Modules and credits Standard ML, APL and Haskell for its constructs.

Syntactically, Python was unique in not taking on many braces or brackets as C, Lisp and Java would. It introduced keywords such as and and or rather than && and ||. This is inline with Python's philosophy, which we'll dive into later.

Python is fairly different from many of its predecessors, though the language Guido wanted to be most different from is Perl. TMTOWTDI (pronounced "Tim Toady") is a Perl motto which stands for "There's more than one way to do it". One of Python's design principles, published in the "Zen of Python" in 1999 is "There should be one — and preferably only one — obvious way to do it", directly conflicting with Perl.

Also, it was influenced by some actual art. Specifically, Python was named after Monty Python.

Oh yeah there are some people you should know

- Guido van Rossum. Benevolent Dictator for Life, until of course he stepped down on 12 July 2018 and now sits on a steering council of five.

- Tim Peters. Made Timsort (what Python and V8 uses). Wrote the Zen of Python, was on Python's board of directors from 2001-2014 and got involved in the early 1990s.

- Barry Warsaw. Core Python developer since mid 90's. Used to be the lead maintainer of Jython, a Java implementation of Python. Currently employed by LinkedIn to work on Python.

Case Study: The Increment/Decrement Operators

Many question why in Python one cannot do x++ or x-- especially since it's a common thing for people to know, is less characters than x += 1, etc etc. Its existence not hugely relevant to Python programmers, but the reasons why it doesn't exist reveals a lot about Python.

- Zen of Python "There should be one — and preferably only one — obvious way to do it".

- ABC never had that operator, so it may have been a fairly intuitive decision.

- It might've been implemented by C just for an optimization as the instructions for

x++could be more easily optimized (source). - Python is serious about keeping its LL parser, which would make

++a bit a pain to differentiate from+ +. (--3will evaluate to3in Python)

The most obvious reason of course, is that Guido didn't want anyone making Python++.

Some Weird Shit: For...Else

for i in range(42):

if i == -1:

print("This will not happen")

break

else:

print("Will this?")

The answer is yes, yes it does happen!

If a loop does not break, Python will try to go to an else block.

Is this a stupid feature? Probably. There seems to be just... a bunch of better and more readable ways to do this. I'm not even going to give an example since there are so many reasons why you might want this kind of logic flow.

Let's not forget that brilliant Zen of Python line. "There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it." Not only are there many ways to do this, a for...else statement is certainly the least obvious way.

The Zen of Python has many thoughts. The follow up to that line is "Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch." The Dutch is referring to none other than Guido himself. So yeah, maybe this is just a mistake that Python made and can never walk back from, since there are definitely people out there using this thing. You can read the mailing list issue about it here (https://mail.python.org/pipermail/python-ideas/2009-October/006155.html)

But how did it end up here in the first place you ask?

Basically this kind of thing became a feature because Donald Knuth used it, and everyone knew about what Donald Knuth does so it made sense. It also made more sense when people used gotos to model their logic flow more frequently as all the loops had a if statement and goto.

The entire for...else block can logically be thought of one piece of code, and the break just jumps to the end and ignores the else. If it doesn't break, then it continues to the else block. You can also try...else!

The Zen of Python

Now that we've talked about two points of the text, let's look at the whole thing.

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

You can get the Zen of Python in a handy Easter Egg, by writing import this. I'll let you think about the irony of that easter egg (line 2 cough cough). Oh and that line I've brought up over and over again? It does something two ways, neither of which are obvious!

I know you probably don't care how the Easter Egg was implemented, since well, it's a string. But you should, because it looks like this;

s = """Gur Mra bs Clguba, ol Gvz Crgref

Ornhgvshy vf orggre guna htyl.

Rkcyvpvg vf orggre guna vzcyvpvg.

Fvzcyr vf orggre guna pbzcyrk.

Pbzcyrk vf orggre guna pbzcyvpngrq.

Syng vf orggre guna arfgrq.

Fcnefr vf orggre guna qrafr.

Ernqnovyvgl pbhagf.

Fcrpvny pnfrf nera'g fcrpvny rabhtu gb oernx gur ehyrf.

Nygubhtu cenpgvpnyvgl orngf chevgl.

Reebef fubhyq arire cnff fvyragyl.

Hayrff rkcyvpvgyl fvyraprq.

Va gur snpr bs nzovthvgl, ershfr gur grzcgngvba gb thrff.

Gurer fubhyq or bar-- naq cersrenoyl bayl bar --boivbhf jnl gb qb vg.

Nygubhtu gung jnl znl abg or boivbhf ng svefg hayrff lbh'er Qhgpu.

Abj vf orggre guna arire.

Nygubhtu arire vf bsgra orggre guna *evtug* abj.

Vs gur vzcyrzragngvba vf uneq gb rkcynva, vg'f n onq vqrn.

Vs gur vzcyrzragngvba vf rnfl gb rkcynva, vg znl or n tbbq vqrn.

Anzrfcnprf ner bar ubaxvat terng vqrn -- yrg'f qb zber bs gubfr!"""

d = {}

for c in (65, 97):

for i in range(26):

d[chr(i+c)] = chr((i+13) % 26 + c)

print("".join([d.get(c, c) for c in s]))

Nice one Tim.

Some Actual History: 1991 to 2000

- February 1991: 0.9.0 published to alt.sources

- January 1994: Python 1.0

- 1995: Numpy (Numeric at the time)

- 30 April 1999: Non font-size changing CSS added to docs. THE NEW AGE OF THE INTERWEBS!

- 16 October 2000: Python 2.0

Could I get the time? What's that, it's False?

From the Python 3.5 changelog;

Before Python 3.5, a datetime.time object was considered to be false if it represented midnight in UTC. This behavior was considered obscure and error-prone and has been removed in Python 3.5.

Umm, ok I guess. This wasn't really a mistake, this behaviour was correctly documented. And, it's consistent behaviour ish. 0 in general is a falsy thing. 0, [], etc etc.

It was actually raised as an issue in 2012, by someone who thought it was a bug. It was passed on because of the reasons stated above, but people came back about this in 2014! Particularly, this weird behaviour made doing if timeobj (where timeobj might be set to some falsy value) useless. Someone made a good argument that this type of 0 shouldn't count the way that others do, as time cannot really be multiplied and such and thus doesn't really represent a numeric value in the traditional sense. It wasn't fixed (released) until September 2015!

Some Actual History: 2000 to 2010

- January 17, 2001: Jython was created

- 2003: BOOLEANS CAME TO PYTHON! Oddly late, C got their booleans in 1999. Also it's implemented as a subclass of Integer, since 0 and 1 is what people used before and that's why you can do arithmetic with Booleans!

- 2005: Django, a popular web framework was born.

- December 2005: Reddit written in Python <3

- 2006: Python 3 development commences

- 2007: Pypy, a JIT compiled super fast Python that can't actually run most production applications for various reasons was released.

- June 2007: Dropbox starts building in Python

- 2008: EOL for Python 2 declared for 2015.

- 3 December 2008: Python 3.0

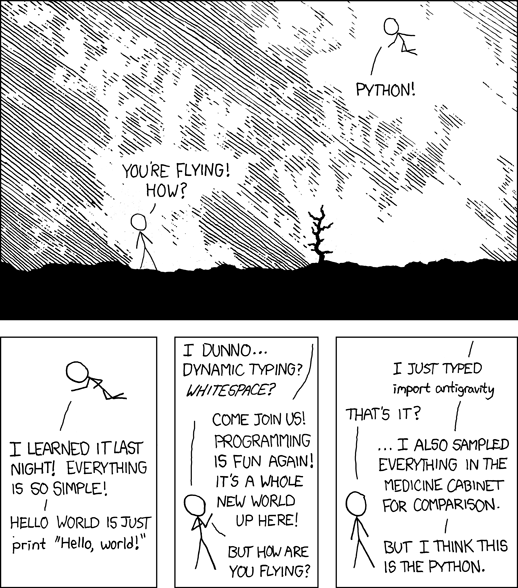

Also, Randall Munroe

import antigravity

Doing that will open a page with this image;

Here's how it's implemented;

import webbrowser

import hashlib

webbrowser.open("https://xkcd.com/353/")

def geohash(latitude, longitude, datedow):

'''Compute geohash() using the Munroe algorithm.

>>> geohash(37.421542, -122.085589, b'2005-05-26-10458.68')

37.857713 -122.544543

'''

# https://xkcd.com/426/

h = hashlib.md5(datedow).hexdigest()

p, q = [('%f' % float.fromhex('0.' + x)) for x in (h[:16], h[16:32])]

print('%d%s %d%s' % (latitude, p[1:], longitude, q[1:]))

We have Skip Montanaro (recently retired, congrats!) to thank for this!

Some Actual History: 2010 to Present

- 2012: Skulpt, an entirely in-browser implementation of Python was created. Pretty wild project if you ask me.

- 2013: Guido goes to Dropbox!

- 2014: January 1, 2020 declared as EOL for Python2, only five years late!

- November 9, 2015: Tensorflow (ML library built by Google) was released.

- October 2016: PyTorch was released (built by Facebook)

- July 2018: Guido steps down as BFDL

- 2018: RustPython, a python interpreter written in Rust comes into existence.

- January 2019: Steering Council Elected

- October 2019: Guido leaves Dropbox

- January 1st 2020: GOODBYE PYTHON 2. New decade, new Python.

This Used to be Silly Episode 2: the GIL

The GIL is silly! Well, no not really it's pretty important and hard to remove. The Global Interpreter Lock makes it so that Python code cannot actually be executed in parallel, so threads are executed concurrently in a way where they're "running at the same time", but never both running at a given time.

It's not just a "Python was implemented this way so we're stuck with it" thing going on here. Pypy came along and it kept the GIL. Ruby has a GIL. OCaml has a GIL. JS just...doesn't have threads. Yeah yeah, IronPython and Jython got rid of the GIL, but I'd like to hammer it in that there is a great argument for the GIL to be great.

So the silly part is what it was like before Python 3.2.

If you were to divide work between two threads, you'd imagine that it would be slightly slower than having one thread run it, since the time it takes for the GIL to be passed around cannot be <= 0. The keyword there is slightly. What you'd get before Python 3.2 is that it could be twice as slow. Oh no.

A quick description of the problem lies in how the GIL was implemented. The logic for it resulted in a system, where every so often (very often), a thread that might be waiting for the GIL will jump up and scream for the GIL, another thread will probably say "no you can't have it, that's mine" and the other thread will just keep jumping up and down and wasting time. The new implementation used an approach that was a bit more "Ok I'm done with the GIL now, who wants it?".

This is a very high level abstraction and somewhat misleading. But tl;dr the GIL was being silly for a long time and no one fixed it. You can watch Dave Beazely's talk on it.

Hall of Fame of things that were broken for a long time and no one noticed non-Python related

- Tim Peters is brilliant not only for Python but also for Timsort! It's used by Python, JS and the millions of Java things. That algorithm was designed in 2002. In 2015, some guys tried to formally verify it, and found it was broken! Link to paper

- The

left-padshenanigans. Basically, npm didn't have any fallback or handling if the dependency of a dependency of a... got removed. So when the tiniest package left npm, everything exploded! Most apps just stopped running. Rust with their package manager cargo just didn't let people remove packages (not in a breaking way at least), somehow npm missed that. - Knight Capital had a bug that disrupted the NYSE and also lost them $460 million! This isn't the strict definition of broken, but there was so much broken in their systems that I have 0 surprise this happened. They received 97 emails about an incorrect configuration after a deploy at 8AM, an hour before trading opened which should've been good warning to rollback, delay or at least throttle. By 10AM, the 460 million was lost. They let that shit run for 45 minutes! The error occurred because devops team failed to update one of the 8 servers. The old code that caused the failure had been obsolete for 9 years. Dead code should be considered a bug, thank you.

Legacy

Julia

Julia quotes "We want something as usable for general programming as Python" on their Why We Created Julia post. Though Julia is fundamentally different by being JITed-ish and more static, their common use in data science showcases some fundamental similarities.

Ruby

The creator of Ruby, Matz said "I wanted a scripting language that was more powerful than Perl, and more object-oriented than Python". It took on a similar engineering path by having a VM (YARV) and creating bytecode for it! Ruby also has a lot of similar syntax such as not having brackets and built itself a very large standard library. A huge difference however, is that Ruby has a lot more complicated grammer (probably inherited through Perl, along with some other crap) through the use of an LALR parser instead of Python's home-grown LL parser.

Go

Several companies have actually migrated from Python to Go, a symbol of success for Go. On their FAQ they list a few reasons as to how Python affected them. The big thing was that go wanted static typing, while keeping a "fluid" language the way Python does. This is a huge win for Go, as I feel a large part of their goal is to encourage good code (and there's a general consensus that typing is good for that). Unlike many other languages that are more recently made, Go keeps the braces. Go basically ran away from all the fluidity that Python, Ruby and Julia have.

Dropbox has migrated some important components to Go, along with maintaining Go packages. Twitch rewrote their IRC chat system in Go. Uber rewrote some vital datastores workers in Go.

End of Post Ramble

In general, syntax is a big one for Python's influence, with CoffeeScript and Swift joining the list.

Python's usage in machine learning is the one thing that will keep Python in the history books. When the future aliens or whatnot study the development of AI, they'll remember the language that footed it.

Python has also footed pieces of internet history, including Wikipedia, Facebook, Amazon and Google. Though it may not be in the history books, Doki Doki Literature Club is a popular video game built in Python and maybe it'll be games like that to make a retro comeback the same way we have emulators for old consoles today!

I tried to come up with a tl;dr to this post, but I don't really have one. I started writing with the intention of showing people how important Python will be to history, but I got carried away with random Python stuffs in my head but I guess that's fine.

I cited sources / provided additional content where I deemed it would be helpful (ie hard to find with a quick Google). If anyone has questions about anything, please email me with your name at kipp dot ly. I did quite a bit of research on everything I wrote here.